| jupyter | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Author: Kenneth Wong (kennethwong12.netlify.app)

Last Edited: 2021-10-25

## For checking python environment

!which python3In this lab, you'll learn how to:

- navigate Jupyter notebooks (like this one);

- write and evaluate some basic expressions in Python, the computer language of the course;

- call functions to use code other people have written; and

- break down Python code into smaller parts to understand it.

This is a question similar to asking why

Programming is a way to “instruct the computer to perform various tasks”.

“Instruct the computer”: this basically means that you provide the computer a set of instructions that are written in a language that the computer can understand. The instructions could be of various types. For example:

- Adding 2 numbers,

- Rounding off a number, etc.

Just like we humans can understand a few languages (English, Spanish, Mandarin, French, etc.), so is the case with computers. Computers understand instructions that are written in a specific syntactical form called a programming language.

“Perform various tasks”: the tasks could be simple ones like we discussed above (adding 2 numbers, rounding off a number) or complex ones which may involve a sequence of multiple instructions. For example:

- Calculating simple interest, given principal, rate and time.

- Calculating the average return on a stock over the last 5 years.

The above 2 tasks require complex calculation. They cannot usually be expressed in simple instructions like adding 2 numbers, etc.

This webpage is called a Jupyter notebook. A notebook is a place to write programs and view their results, and also to write text. Thus, it allows presentation of text and graphics combined with Python code that can be run interactively, with the results appearing inline. As you can see, it works as an interactive environment that runs within your web browser.

You'll just need to use command prompt for the sake of opening the jupyter notebook. No more than that is required.

To begin using a Jupyter Notebook on your own computer, you need to launch a command prompt (or command shell). If you don't know what this is, you'll need to get familiar with the command prompt and navigating around on your computer using change directory commands, in order to be able to launch the notebook. The Lab computers have been upgraded to Windows 10. In this version of Windows, there are multiple ways to open a command prompt - nicely explained here: http://www.howtogeek.com/235101/10-ways-to-open-the-command-prompt-in-windows-10/. There is also a good reference for the command prompt in Windows: http://dosprompt.info/

On a mac, you can launch the terminal app. Once you have a shell, navigate (change directory) to whatever directory you want to work in. . On a mac, the syntax is a bit different since it is based on Linux. Here is a reference for commands on the mac: http://ss64.com/osx/, or a simpler version here: http://www.dummies.com/how-to/content/how-to-use-basic-unix-commands-to-work-in-terminal.html.

Save the notebook you need to somewhere in the disk, like Downloads, or some other location (but just remember where you put it). At the command prompt, cd to that location, and type:

jupyter notebookOnce you launch the Jupyter Notebook, and the Notebook opens up in your browser, you will be looking at a directory of the folder you were in when you launched the notebook. you can either load an existing notebook if you see one in the directory, or create a new one. If you changed directory to the correct location, you should already see this notebook in the directory in the Jupyter Notebook:

XXX.ipynbThe ipynb is a reference to the older name of IPython Notebook for the Jupyter notebooks.

If you click on this entry in the directory within the Jupyter Notebook, another tab will be created in your browser, containing this notebook, ready to use. Go ahead and do that.

Note that it has cells, that contain text (until farther down in the notebook). These are markdown cells.

In a notebook, each rectangle containing text or code is called a cell.

Text cells (like this one) can be edited by double-clicking on them. They're written in a simple format called Markdown to add formatting and section headings. You don't need to learn the details of Markdown here.

After you edit a text cell, click the "run cell" button at the top that looks like ▶| or hold down shift + return to confirm any changes. (Try not to delete the instructions of the lab.)

Other cells contain code in the Python 3 language. Running a code cell will execute all of the code it contains.

To run the code in a code cell, first click on that cell to activate it. It'll be highlighted with a little green or blue rectangle. Next, either press ▶| or hold down shift + enter.

Try running this cell:

print("Hello, World!")print("\N{WAVING HAND SIGN}, \N{EARTH GLOBE ASIA-AUSTRALIA}!")The fundamental building block of Python code is an expression. Cells can contain multiple lines with multiple expressions. When you run a cell, the lines of code are executed in the order in which they appear. Every print expression prints a line. Run the next cell and notice the order of the output.

print("First this line is printed,")

print("and then this one.")You can use Jupyter notebooks for your own projects or documents. When you make your own notebook, you'll need to create your own cells for text and code.

To add a cell, click the + button in the menu bar. It'll start out as a text cell. You can change it to a code cell by clicking inside it so it's highlighted, clicking the drop-down box next to the restart (⟳) button in the menu bar, and choosing "Code".

Question: Add a code cell below this one. Write code in it that prints out:

A whole new cell! ♪🌏♪

(That musical note symbol is like the Earth symbol. Its long-form name is \N{EIGHTH NOTE}.)

Run your cell to verify that it works.

### TODO: ANSWER HERE ###Question: Change the block below so that it prints out:

First this line,

then the whole 🌏,

and then this one.

### TODO: ANSWER HERE ###Python is a language, and like natural human languages, it has rules. It differs from natural language in two important ways:

- The rules are simple. You can learn most of them in a few weeks and gain reasonable proficiency with the language in a semester.

- The rules are rigid. If you're proficient in a natural language, you can understand a non-proficient speaker, glossing over small mistakes. A computer running Python code is not smart enough to do that.

Whenever you write code, you'll make mistakes. When you run a code cell that has errors, Python will sometimes produce error messages to tell you what you did wrong.

Errors are okay; even experienced programmers make many errors. When you make an error, you just have to find the source of the problem, fix it, and move on.

We have made an error in the next cell. Run it and see what happens.

print("This line is missing something."print("This line is missing something.")Note: In the toolbar, there is the option to click Cell > Run All, which will run all the code cells in this notebook in order. However, the notebook stops running code cells if it hits an error, like the one in the cell above.

The last line of the error output attempts to tell you what went wrong. The syntax of a language is its structure, and this SyntaxError tells you that you have created an illegal structure. "EOF" means "end of file," so the message is saying Python expected you to write something more (in this case, a right parenthesis) before finishing the cell.

There's a lot of terminology in programming languages, but you don't need to know it all in order to program effectively. If you see a cryptic message like this, you can often get by without deciphering it. (Of course, if you're frustrated, ask a neighbor or a staff member for help.)

Try to fix the code above so that you can run the cell and see the intended message instead of an error.

The kernel is a program that executes the code inside your notebook and outputs the results. In the top right of your window, you can see a circle that indicates the status of your kernel. If the circle is empty (⚪), the kernel is idle and ready to execute code. If the circle is filled in (⚫), the kernel is busy running some code.

Next to every code cell, you'll see some text that says In [...]. Before you run the cell, you'll see In [ ]. When the cell is running, you'll see In [*]. If you see an asterisk (*) next to a cell that doesn't go away, it's likely that the code inside the cell is taking too long to run, and it might be a good time to interrupt the kernel (discussed below). When a cell is finished running, you'll see a number inside the brackets, like so: In [1]. The number corresponds to the order in which you run the cells; so, the first cell you run will show a 1 when it's finished running, the second will show a 2, and so on.

You may run into problems where your kernel is stuck for an excessive amount of time, your notebook is very slow and unresponsive, or your kernel loses its connection. If this happens, try the following steps:

- At the top of your screen, click Kernel, then Interrupt.

- If that doesn't help, click Kernel, then Restart. If you do this, you will have to run your code cells from the start of your notebook up until where you paused your work.

- If that doesn't help, restart your server. First, save your work by clicking File at the top left of your screen, then Save and Checkpoint. Next, click Control Panel at the top right. Choose Stop My Server to shut it down, then Start My Server to start it back up. Then, navigate back to the notebook you were working on. You'll still have to run your code cells again.

Quantitative information arises everywhere in data science. In addition to representing commands to print out lines, expressions can represent numbers and methods of combining numbers. The expression 3.2500 evaluates to the number 3.25. (Run the cell and see.)

3.2500

Notice that we didn't have to print. When you run a notebook cell, if the last line has a value, then Jupyter helpfully prints out that value for you. However, it won't print out prior lines automatically.

print(2)

3

4Above, you should see that 4 is the value of the last expression, 2 is printed, but 3 is lost forever because it was neither printed nor last.

You don't want to print everything all the time anyway. But if you feel sorry for 3, change the cell above to print it.

The line in the next cell subtracts. Its value is what you'd expect. Run it.

3.25 - 1.5Many basic arithmetic operations are built into Python. This chapter of the Data 8 course web book describes the most common arithmetic operators used. The common operator that differs from typical math notation is **, which raises one number to the power of the other. So, 2**3 stands for

The order of operations is the same as what you learned in elementary school, and Python also has parentheses. For example, compare the outputs of the cells below. The second cell uses parentheses for a happy new year.

4+6*5-6*3**2*2**3/4*74+(6*5-(6*3))**2*((2**3)/4*7)In standard math notation, the first expression is

while the second expression is

Question: Write a Python expression in this next cell that's equal to

Replace the block below with your expression. Try to use parentheses only when necessary.

Hint: The correct output should start with a familiar number.

### TODO: ANSWER HERE ###In natural language, we have terminology that lets us quickly reference very complicated concepts. We don't say, "That's a large mammal with brown fur and sharp teeth!" Instead, we just say, "Bear!"

In Python, we do this with assignment statements. An assignment statement has a name on the left side of an = sign and an expression to be evaluated on the right.

ten = 3 * 2 + 4When you run that cell, Python first computes the value of the expression on the right-hand side, 3 * 2 + 4, which is the number 10. Then it assigns that value to the name ten. At that point, the code in the cell is done running.

=is an assignment of a value to a variable.

After you run that cell, the value 10 is bound to the name ten:

tenThe statement ten = 3 * 2 + 4 is not asserting that ten is already equal to 3 * 2 + 4, as we might expect by analogy with math notation. Rather, that line of code changes what ten means; it now refers to the value 10, whereas before it meant nothing at all.

If the designers of Python had been ruthlessly pedantic, they might have made us write

define the name ten to hereafter have the value of 3 * 2 + 4

instead. You will probably appreciate the brevity of "="! But keep in mind that this is the real meaning.

Question: Try writing code that uses a name (like eleven) that hasn't been assigned to anything. You'll see an error!

### ANSWER HERE ###A common pattern in Jupyter notebooks is to assign a value to a name and then immediately evaluate the name in the last line in the cell so that the value is displayed as output.

close_to_pi = 355/113

close_to_pisemimonthly_salary = 841.25

monthly_salary = 2 * semimonthly_salary

number_of_months_in_a_year = 12

yearly_salary = number_of_months_in_a_year * monthly_salary

yearly_salaryNames in Python can have letters (upper- and lower-case letters are both okay and count as different letters), underscores, and numbers. The first character can't be a number (otherwise a name might look like a number). And names can't contain spaces, since spaces are used to separate pieces of code from each other.

Other than those rules, what you name something doesn't matter to Python. For example, this cell does the same thing as the above cell, except everything has a different name:

a = 841.25

b = 2 * a

c = 12

d = c * b

dHowever, names are very important for making your code readable to yourself and others. The cell above is shorter, but it's totally useless without an explanation of what it does.

Now that you know how to name things, you can start using the built-in tests to check whether your work is correct. Sometimes, there are multiple tests for a single question, and passing all of them is required to receive credit for the question. Please don't change the contents of the test cells.

Go ahead and attempt Question 3.2. Running the cell directly after it will test whether you have assigned seconds_in_a_decade correctly in Question 3.2. If you haven't, this test will tell you the correct answer. Resist the urge to just copy it, and instead try to adjust your expression. (Sometimes the tests will give hints about what went wrong...)

**Question 3.2.** Assign the name `seconds_in_a_decade` to the number of seconds between midnight January 1, 2010 and midnight January 1, 2020. Note that there are two leap years in this span of a decade. A non-leap year has 365 days and a leap year has 366 days.

*Hint:* If you're stuck, the next section shows you how to get hints.

<!--

BEGIN QUESTION

name: q32

--># Change the next line

# so that it computes the number of seconds in a decade

# and assigns that number the name, seconds_in_a_decade.

seconds_in_a_decade = ...

# We've put this line in this cell

# so that it will print the value you've given to seconds_in_a_decade when you run it.

# You don't need to change this.

seconds_in_a_decadeYou may have noticed these lines in the cell in which you answered Question 3.2:

# Change the next line

# so that it computes the number of seconds in a decade

# and assigns that number the name, seconds_in_a_decade.

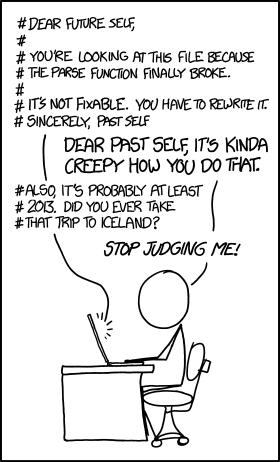

This is called a comment. It doesn't make anything happen in Python; Python ignores anything on a line after a #. Instead, it's there to communicate something about the code to you, the human reader. Comments are extremely useful.

Source: https://xkcd.com/1421/

The most common way to combine or manipulate values in Python is by calling functions. Python comes with many built-in functions that perform common operations.

For example, the abs function takes a single number as its argument and returns the absolute value of that number. Run the next two cells and see if you understand the output.

abs(5)

abs(-5)

Chunhua is on the corner of 7th Avenue and 42nd Street in Midtown Manhattan, and she wants to know far she'd have to walk to get to Gramercy School on the corner of 10th Avenue and 34th Street.

She can't cut across blocks diagonally, since there are buildings in the way. She has to walk along the sidewalks. Using the map below, she sees she'd have to walk 3 avenues (long blocks) and 8 streets (short blocks). In terms of the given numbers, she computed 3 as the difference between 7 and 10, in absolute value, and 8 similarly.

Chunhua also knows that blocks in Manhattan are all about 80m by 274m (avenues are farther apart than streets). So in total, she'd have to walk

Question 4.1.1. Fill in the line num_avenues_away = ... in the next cell so that the cell calculates the distance Chunhua must walk and gives it the name manhattan_distance. Everything else has been filled in for you. Use the abs function. Also, be sure to run the test cell afterward to test your code.

# Here's the number of streets away:

num_streets_away = abs(42-34)

# Compute the number of avenues away in a similar way:

num_avenues_away = ...

street_length_m = 80

avenue_length_m = 274

# Now we compute the total distance Chunhua must walk.

manhattan_distance = street_length_m*num_streets_away + avenue_length_m*num_avenues_away

# We've included this line so that you see the distance you've computed

# when you run this cell.

# You don't need to change it, but you can if you want.

manhattan_distanceSome functions take multiple arguments, separated by commas. For example, the built-in max function returns the maximum argument passed to it.

max(2, -3, 4, -5)Function calls and arithmetic expressions can themselves contain expressions. You saw an example in the last question:

abs(42-34)

has 2 number expressions in a subtraction expression in a function call expression. And you probably wrote something like abs(7-10) to compute num_avenues_away.

Nested expressions can turn into complicated-looking code. However, the way in which complicated expressions break down is very regular.

Suppose we are interested in heights that are very unusual. We'll say that a height is unusual to the extent that it's far away on the number line from the average human height. An estimate of the average adult human height (averaging, we hope, over all humans on Earth today) is 1.688 meters.

So if Kayla is 1.21 meters tall, then her height is

And here's how we'd write that in one line of Python code:

abs(1.21 - 1.688)What's going on here? abs takes just one argument, so the stuff inside the parentheses is all part of that single argument. Specifically, the argument is the value of the expression 1.21 - 1.688. The value of that expression is -.478. That value is the argument to abs. The absolute value of that is .478, so .478 is the value of the full expression abs(1.21 - 1.688).

Picture simplifying the expression in several steps:

abs(1.21 - 1.688)abs(-.478).478

In fact, that's basically what Python does to compute the value of the expression.

Question 5.1. Say that Paola's height is 1.76 meters. In the next cell, use abs to compute the absolute value of the difference between Paola's height and the average human height. Give that value the name paola_distance_from_average_m.

# Replace the ... with an expression

# to compute the absolute value

# of the difference between Paola's height (1.76m) and the average human height.

paola_distance_from_average_m = ...

# Again, we've written this here

# so that the distance you compute will get printed

# when you run this cell.

paola_distance_from_average_mNow say that we want to compute the more unusual of the two heights. We'll use the function max, which (again) takes two numbers as arguments and returns the larger of the two arguments. Combining that with the abs function, we can compute the larger distance from average among the two heights:

# Just read and run this cell.

kayla_height_m = 1.21

paola_height_m = 1.76

average_adult_height_m = 1.688

# The larger distance from the average human height, among the two heights:

larger_distance_m = max(abs(kayla_height_m - average_adult_height_m), abs(paola_height_m - average_adult_height_m))

# Print out our results in a nice readable format:

print("The larger distance from the average height among these two people is", larger_distance_m, "meters.")The line where larger_distance_m is computed looks complicated, but we can break it down into simpler components just like we did before.

The basic recipe is to repeatedly simplify small parts of the expression:

- Basic expressions: Start with expressions whose values we know, like names or numbers.

- Examples:

paola_height_mor5.

- Examples:

- Find the next simplest group of expressions: Look for basic expressions that are directly connected to each other. This can be by arithmetic or as arguments to a function call.

- Example:

kayla_height_m - average_adult_height_m.

- Example:

- Evaluate that group: Evaluate the arithmetic expression or function call. Use the value computed to replace the group of expressions.

- Example:

kayla_height_m - average_adult_height_mbecomes-.478.

- Example:

- Repeat: Continue this process, using the value of the previously-evaluated expression as a new basic expression. Stop when we've evaluated the entire expression.

- Example:

abs(-.478)becomes.478, andmax(.478, .072)becomes.478.

- Example: